by Marianna Michell – 11th May 2025

Twenty years ago, after leaving this church to enter ministry training in Manchester, I was living in the Rossendale valley in Lancashire – just over the moors from where I grew up near Nelson.

Rawtenstall Unitarian church is a modern and strange-looking building on a rise off the main street of that town. At the time, the congregation was served by a retired Unitarian minister, Rev. Dr. David Doel, who quietly stepped aside to allow me to participate in their fortnightly services.

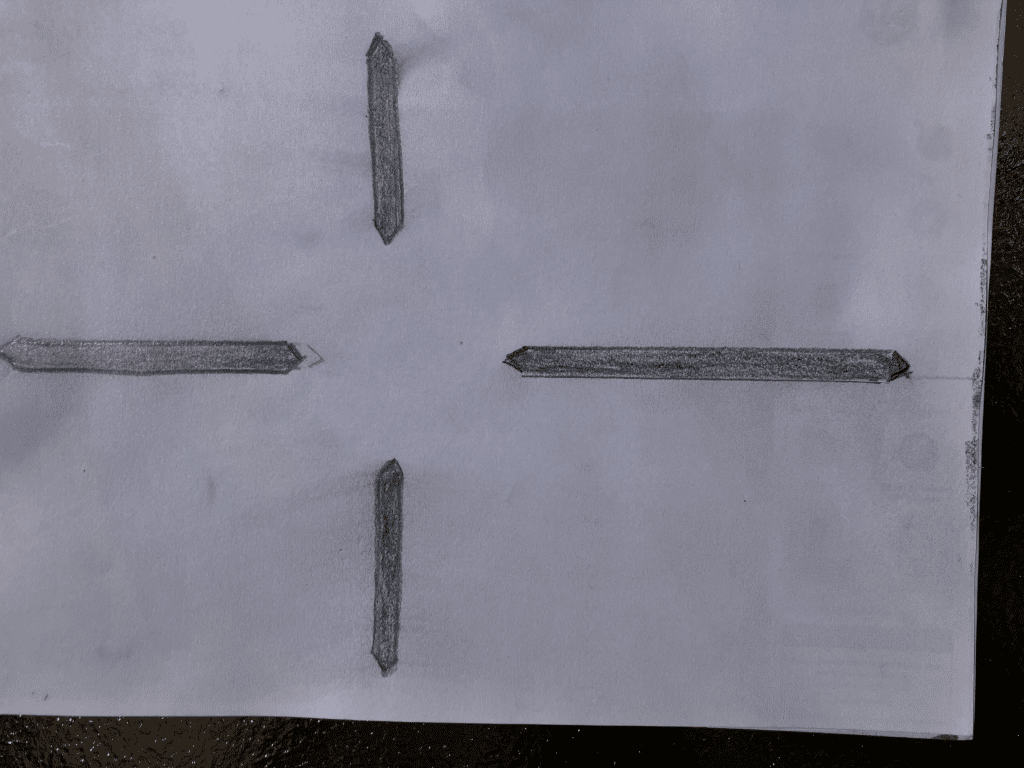

Shortly after I moved to the valley, David developed a chest infection, and I was asked to replace him at two days’ notice. I had been impressed already by a cross placed on the back wall of the church, not centrally, but to the side. It had been commissioned for the church building when new. This is the image you have on a little sheet of paper.

Please take a minute to explore the image for yourselves….

It is not a crucifix – there is no body; and a cross is not exclusively a Christian image but an Everyman image; and this cross has four limbs, not two.

The vertical limbs arrow upwards and downwards; the horizontals point outwards and inwards. And there is no crossing point – no conflict? And so, the centre is non-specific, unclaimed.

That centre asks questions. It is like an icon. Contemplating it can leave us feeling peaceful: there is no prescription in the centre for what we should think. Deep calls to deep.

And so, to a Child’s vision of heaven. The piece I play after the talk is the very final part of Mahler’s 4th symphony, entitled in translation ‘The heavenly life’. A soprano sings about Jesus’ female disciples. In Heaven, they seem to be doing the same tasks as on Earth. This is the Heaven that others have told her about, with her imagination thrown in. Though there is muddle about God and eternity, the music itself holds the child’s sense of wonder.

Recently, I read a talk by a Dutch so-called ‘atheist’ minister, Rev. Klaas Hendricks, ‘Upbringing and Tradition.’ Our Minister, Andrew, has included it on the church website.

“For me, God is not a being but a word for what can happen between people.”

He quotes the well-known biblical lines, ‘When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I reasoned like a child. Now that I am an adult I have left behind all childish things.’

I was never comfortable with those lines – as if a child has no innate wisdom – it reminded me of the novel ‘Hard Times’ by Dickens, where a child is seen as an empty vessel, to be filled with ‘facts, facts, facts.’

Klaas Hendriks also interpreted it differently: ‘what others heard me say, back then, I had picked up from what had ben said to me.’ I remember my mother telling me off because I’d go to her and say, ‘People say….’

And Hendriks continues, ‘as an adult, what others hear me say now, comes from me, spoken from my own experience.’

And he asks, ‘Do you remember when God entered your life, initially in the form of your parents, as carers and exemplars of what life was about? Later, though, they were the ones from whom you had to separate yourself.’

And then, ‘Those from liberal backgrounds are not burdened by stern images of a God, keeping a tally of wrongdoing. Those who became liberal later had more to deal with along the way. The more that ‘tradition’ had formed their lives, the longer the journey towards finding meaning for themselves.’ I can identify with that.

‘You can’t fool children. If your words don’t match you, they will spot it instantly.

That is like those occasions when a weary parent skips out a bit of the familiar bedtime story, but the child leaps in, not allowing the parent to miss it out. She needs to hear it all, not some garbled and inauthentic story.

Klaak Hendriks’ talk prompted an early memory for me – a moment caught as if by a camera. I was four, and we were waving off a van which contained the remains of my granny’s dog, Peggy.

Granny, and my parents and I, lived next door to each other, and I have a photo of mum holding me. I am just a few days old. She is standing in the middle of the road – no traffic at all except the occasional van or horse-and-cart.

In that same place, four years later, Peggy the dog was run over by a horse and cart. I clearly recall watching that van going round the corner, and hearing mum make up a song on the spot, about Peggy going to live with Jesus!

That was the thing about my Sunday School and Chapel-going. Jesus was spoken of constantly. Who was this Lord, Saviour, Messiah, Jehovah, God, and which was which?

I asked mum a few questions about where heaven was, where Peggy went to be with Jesus. If it was up in the sky, how do you get there?

A child’s imagination is based on something known – as in the soprano part of that symphony where she sings of the earthly life of saints. I cannot recall any sensible answer to my question, so I had to invent the scenario. It sounds ridiculous now, but this was a genuine childhood effort to sort things out…

I saw in my mind’s eye a series of old rickety wooden ladders strapped together and all waving up there into the great blue yonder. At the top was a hen-hut (our neighbour had lots of hen-huts, all visible just beyond our garden).

And Jesus was in this hut, and it was dark. There was no space for people, and I could not see Peggy the dog. And I was scared it might all wobble over in the breeze, just as my childhood acceptance of inauthentic religion wobbled over within a few years.

At around 10, I reckoned the young Sunday School teachers did not dare to think that Jesus not only ate fish by the seashore, but that he also needed to go for a wee like everyone else.

This whole religious story was unsatisfactory: false explanations imply that children do not hold their own wisdom or sensibility; thus, that sensibility becomes replaced by some official version.

Some of you may understand children as having different souls – even twins are individual; though they may bring knowledge and richness with them, they learn instead that the external world is what matters. Certainly, it is what we make of the world around us, that matters.

But if in your understanding, we come into the world unencumbered by earlier memory, then it is no less true that a new baby is dependent on others; and so, parents and society slowly distort a child’s natural understanding.

My youthful understanding of Jesus fought with my upbringing. We lived in a village at the centre of which sat a ‘Particular Baptist’ chapel. This mismatch drove me both inside myself, and out into nature.

The design of that cross also takes us inwards; yet it also points outwards in all directions. We live out there in the world, but in the centre is our still reference point.

Now, that label, ‘Particular Baptist’. You may know that one of the streams of religious thought which flowed into the UK Unitarian movement, was that of the General Baptists. To them, Christ died for all people, but Particular Baptists said that only particular people were due to be saved. That was the chapel and the Sunday School that I was forced to attend till I was 18…..

We all arise from different family influences, yet we bring our personal thinking into play, modifying what we have been told when young. By speaking with quiet confidence from our authentic voices, we give courage to others to do the same. It does away with a whole lot of dishonest conversation.

At the very ground of our being is space, just as in the centre of that unusual cross at Rawtenstall Church: a space where colours we cannot describe might exist, where thoughts move and dissolve, but where doctrine and outer control are simply redundant. It is a space for contemplation.

And so, I leave you with what is often referred to as the ‘God-shaped-hole’ but I wonder, if that word ‘God’ is not a helpful one, do you have a favoured replacement?