A winter’s day pilgrimage-cum-treasure-hunt to meet with some Straw Bears and to follow a plough

READINGS: Matthew 13:44-52 (trans. David Bentley Hart)

[Jesus said:] “The Kingdom of the heavens is like a treasure that had been hidden in a field, which a man found and hid, and from his joy he goes and sells the things he owns and purchases that field. Again, the Kingdom of the heavens is like a merchant looking for lovely pearls; And, finding one extremely valuable pearl, he went away and sold all the things he owned and purchased it. Again, the Kingdom of the heavens is like a large dragnet cast into the sea and gathering in things of every kind: And when it was filled they drew it up onto the strand and, sitting down, collected the good things in vessels, but threw the rancid things away. Thus it will be at the consummation of the age: The angels will go forth and will separate the wicked out from the midst of the just, And will throw them into the furnace of fire; there will be weeping and grinding of teeth there. Did you understand all of these things?” [The disciples] say to him, “Yes.” Then he said to them, “Hence every scribe who has been made a disciple of the Kingdom of heavens is like a man who is a master of a house, who brings forth things new and old from his treasury.”

‘The Bright Field’ — R. S. Thomas

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the

pearl of great price, the one field that had

treasure in it. I realise now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

An Introduction to the Whittlesea Straw Bear Festival

In Whittlesea, from when no one quite knows, it was the custom on the Tuesday following Plough Monday (the 1st Monday after Twelfth Night) to dress one of the confraternity of the plough in straw and call him a ‘Straw Bear’. A newspaper of 1882 reports that “. . . he was then taken around the town to entertain by his frantic and clumsy gestures the good folk who had on the previous day subscribed to the rustics, a spread of beer, tobacco and beef.”

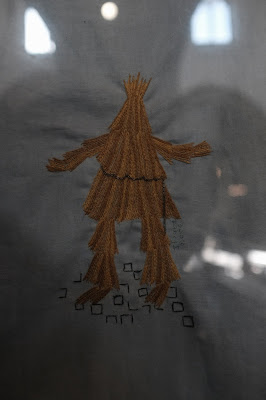

The bear was described as having great lengths of tightly twisted straw bands prepared and wound up the arms, legs and body of the man or boy who was unfortunate enough to have been chosen. Two sticks fastened to his shoulders met a point over his head and the straw wound round upon them to form a cone above the Bear’s head. The face was quite covered and he could hardly see. A tail was provided and a strong chain fastened around the armpits. He was made to dance in front of houses and gifts of money or of beer and food for later consumption was expected. It seems that he was considered important, as straw was carefully selected each year, from the best available, the harvesters saying, “That’ll do for the Bear.”

The tradition fell into decline at the end of the nineteenth century, the last sighting being in 1909 as it appears that an over-zealous police inspector had forbidden Straw Bears as a form of cadging.

The custom was revived in 1980 by the Whittlesea Society, and for the first time in seventy years a Straw Bear was seen on the streets accompanied by his attendant keeper, musicians and dancers, about thirty in all. Various public houses were visited around the town as convenient places for the Bear and dancers to perform in front of an audience — with much needed refreshment available!

—o0o—

A winter’s day pilgrimage-cum-treasure-hunt to meet with some Straw Bears and to follow a plough

One of the sayings of Jesus that early on in my life completely captured my imagination was his suggestion that every scribe who has been made ‘a disciple of the Kingdom of heavens’ is like a woman who is a master of a house, who brings forth things new and old from her treasury. I took, and continue to take, this as an encouragement never to throw away my own inherited old traditions but to see them, potentially anyway, as a treasure house capable of both preserving powerful old insights and wisdom and also generating, almost alchemically, genuinely new forms of them.

As you were reminded in our readings, Jesus’ suggestion almost immediately follows his references, firstly, to a field in which an unnamed treasure has been hidden and, secondly, to a pearl of great price. Consequently, in my mind — and, indeed, in the mind of many others in these British Isles such as the Welsh poet R. S. Thomas — in what consists the ‘treasure house’ is often alchemically transformed into a landscape which, for me, was ‘a field in England’ into which I was called forth in the here and now to bring into the light treasure old and new and to find and uncover pearls of great price.

Thanks to an early diet of esoteric landscape and/or folklore related books, especially those by Alfred Watkins (‘The Old Straight Track’) and Janet and Colin Bord (‘Mysterious Britain’), during the late 1970s and early 1980s the British, but particularly for me the English, landscape had become an alluring, magical and mysterious world into which, by foot or bicycle, my schoolboy self often made his escape. It was to enter a genuinely dynamic, vibrant and creative world which stood in stark contrast to the utterly bleak, destructive, disenchanted, capitalist — and soon to be almost wholly financialised — world that was being conjured into being all around me by Thatcher and Reagan using some dark and destructive spells written by their high priests Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

Although, today, Watkins and the Bords’ books seem to me — and probably to most people — clearly full of some very cranky ideas (e.g. about UFOs and Ley-lines), it’s important to say here that, on a recent re-reading of them, their words still managed to conjure up in me something of the spell they first cast over me as a boy. Here is an example of that call as expressed in the words which conclude Watkins’ last book published in 1932 called ‘Archaic Tracks Round Cambridge’:

Adventure lies lurking in these lines where I point the way for younger feet than mine. Detective work of sorts; unnoticed mark-stones almost buried in the banks of cross-roads, in the field, or on a town pavement; the edges of an unrecorded camp; a faint mound almost levelled; or, again on the ley of the land, as the eye looks straight on, the point of a distant beacon-hill as a mark on the sky-line. Who will strike the trail?

Well, I did! and since then I have never been off the trail. Of course, what I have found along it has been something different from that which Watkins and the Bords thought they had found, but without their work — and, I should add, their black and white photographs which illustrated their books — I would never have set off on my own journey of adventure.

The trail quickly brought me into direct contact with many oral stories, examples of written literature, dances and music that together form a treasury of inspiration from which countless numbers of people in these isles have drawn in their attempts to find things which are truly valuable in life but which, for some reason, are currently lacking. As Rob Young puts it in his recent book ‘Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music’, this treasury of folk traditions form ’[a]n oasis from which to refresh our own art’ (Young, p. 6).

But, forty-odd years on from my first tentative steps on the trail, I find myself, perhaps more than ever before, strongly called into a renewed exploration of the treasury of tradition and the bright fields around me in order to seek for certain values, pearls if you like, which have been both carelessly and deliberately buried by the detritus of the past half-century of our history.

Rob Young’s aforementioned book about British folk music published in 2016 was key catalyst in this renewal of my passion for the trail because he reminded me of the existence of what he calls ‘the silver chains that bind more than a century of music into a continuum’ (Young, p. 7). He goes on to say that:

It’s important to remember . . . that the links in the chain of tradition have been forged by revolutionaries. The great age of folkloric retrieval is synchronous with the age of Karl Marx (Young, p. 7).

Although I’m very critical of many aspects of post-Marx Marxist thought, along with the contemporary political commentator Paul Mason, I find the early ideas of Marx contained in his Paris Manuscripts of 1844, and in pieces like the 1858 ‘Fragment on Machines’ (from The Grundrisse), some very powerful and highly relevant ideas that can be held together under Marx’s single thought that the basic purpose of human beings is to set themselves free. Here, of course, there is an overlap with what is a recurring theme of the whole Bible, namely God’s call to ‘set my people free’ (cf. Genesis 9:1) — a theme which so inspired our radical religious forebears from Lollard to Leveller and on to the Christian Socialists and Tolstoyans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As Paul Mason makes it clear:

The 1844 manuscripts contain an idea lost to Marxism: the concept of communism as “radical humanism”. Communism, said Marx, is not simply the abolition of private property but the “appropriation of the human essence by and for man . . . the complete return of man to himself as a social (i.e., human) being”. But, says Marx, communism is not the goal of human history. It is simply the form in which society will emerge after 40,000 years of hierarchical organisation. The real goal of human history is individual freedom and self-realisation (emphasis mine).

I think Rob Young makes a powerful case that the British folk music and folk-inspired classical and rock music tradition [whether in classical composers like Holst, Vaughan Williams, Delius, Moeran, Ireland, Warlock, Bridge and Butterworth; in more obviously ‘folky’ sounding musicians from the late 1950s and early 1960s like Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Archie Fisher, and Shirley Collins; in the folk-rock bands and musicians of the 1960s and early 70s such as Fairport Convention, Mr Fox, Forest, Incredible String Band, Heron, Pentangle, Traffic, Jethro Tull, Meic Stevens; or in the more contemporary bands from the late 1970s onwards such as Mark Hollis’ ‘Talk Talk’ or the hauntological electronica artists found on the ‘Ghost Box Records’ and ‘Clay Pipe Music’ labels] we find a music shot through with the radically humanist desire to reach the goal of individual freedom and self-realisation.

In our own age which is being marked more and more by authoritarian politics and the repression of individuality in favour of fantasy, monocultural nationalisms, my own desire for freedom and self-realisation (surely also absolutely central to the Unitarian project) without doubt inspired Susanna and me along with an old college friend Graham to make a little pilgrimage-cum-treasure-hunt on Saturday 18th January out into the dark Cambridgeshire fens to meet with and follow the Straw Bears and ancient plough as they made their noisy, wild and festive way around the small town centre filled with musicians, dancers, pilgrims and pearl-hunters like us — including, I should add, at least three other people from this congregation.

The festival is plainly shot through with the radical humanist desire to reach the goal of individual freedom and self-realisation. This is seen in the gentle, but still wild, joy of the processions, it’s heard in the music and seen in the dances, it’s tasted in the plurality of foods and drinks, it’s seen in the styles of dress and demeanour expressed by all the people present, black, white, gay and straight, Eastern and Western European, Indian and East Asian and certainly many others I did not see. I took particular delight in partaking in some very English tea and tea cakes in a packed Chinese Restaurant surrounded by Morris Dancers and musicians fuelling themselves ready to take to the cold streets and invoke the wild spirit of Pan himself. Later on, in the parish church, Christian and pagan intermingled seamlessly over still more tea and cakes. The pubs will have been similarly mixed and wild but since they were rammed full, getting into one of them would have required more time than we had and so the delight of quaffing a pint of real ale in an ancient hostelry was left for another day.

All in all it was a splendid reminder of something noted by the English author, screenwriter, playwright, literary critic and blogger, Peter Jukes, in a fine and powerful recent piece called ‘This is My England And Yours: Reclaiming Englishness’, namely, that

If we’re going to have a Boris Johnson Government run by English nationalists, with English priorities for English voters, let us finally put paid to that narrow and untenable ethnic Englishness that has emerged from the wreckage of Brexit and rescue that other civic and civil England which welcomes strangers and has always accommodated difference.

At it’s best the Straw Bear Festival seems to me to be an example of this living folk tradition of civic tolerance and historic diversity that exists not, of course, only in England, but in all the other countries of the UK.

As we in these ‘spectred isles’ (pun intended) begin, what is to many of us, a regrettable process of national withdrawal and isolation it seems to me that, as outward looking, radical humanists (albeit radical, religious humanists), there is great merit and worth to be found in looking once again into the treasuries of her varied folk traditions and digging into her fertile fields for resources which can help us continue together, in a loose but still real community, genuinely to achieve individual freedom and self-realisation.

But, lest I be accused of falling into an easy and false optimism it’s also vital to remember something else that Rob Young notes in his book. He writes:

The idea of folk still seems unstable, volatile: there’s an ongoing chemical reaction that hasn’t yet subsided. It’s difficult to envisage a time when these internal arguments will cease to define and invigorate Britain’s cultural life. If it is to thrive, and not stagnate, it will continue to need the friction between conservation and progression, city and country, acoustics and electricity, homespun and visionary, familiar and uncanny (Young, pp. 8-9)

His words remind me that, although in Whittlesea I saw and experience much that I do want to bring out of the treasury and dig up from the fields of the folk tradition, there were also present in the mix some regressive and dark elements. Now and then it was possible to experience intimations of English nationalism to which I have already alluded.

Because our folk traditions remain unstable and volatile, those of us who truly wish to become scribes of the Kingdom, or as I’d prefer us to be called, scribes of the Republic of heavens on earth, as Jesus also taught, we need to be ‘wise as serpents and guileless as doves’ (Matthew 10:16) and be very, very careful about exactly what things we choose to bring out of our folk tradition’s treasury and dig out of its fields.

I will finish simply by noting that I was both genuinely uplifted and profoundly disturbed by those Straw Bears. They are truly uncanny, wild, unstable, volatile and liminal creatures capable of acting equally as harbingers of joy and/or woe. They are unresolvable creatures and this is, perhaps, why, in my imagination anyway, the Straw Bears are so powerful and primal.

Simultaneously they help reveal to me visions of both heaven and hell and as a scribe of the Republic of heavens on earth I can only try my best to ensure that the bears are encouraged to lead into being more of heaven than of hell.

With this hope in mind and as the first winter finally begins to draw to a close across a noticeably changed country, it only remains for me to wish you, and all the Straw Bears, ‘Wassail’ and encourage you to put your own hand to the Republic of heavens’ plough so as to bring forth, in time, a fine harvest of individual freedom and self-realization.