Scattering the proud in the imagination of their hearts; putting down the mighty from their seat; exalting the humble and meek; filling the hungry with good things — an Advent address written to outline the task before a progressive, liberal-religious, free-thinking community following Thursday’s General Election (2019)

The Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55) in David Bentley Hart’s translation (2017)

And Mary said, ‘My soul proclaims the Lord’s greatness, and my spirit rejoices in God my saviour, because he looked upon the low estate of his slave. For see: Henceforth all generations will bless me; because the Mighty One has done great things to me. And holy is his name, and his mercy is for generations and generations to those who fear him. He has worked power with his arm, he has scattered those who are arrogant in the thoughts of their hearts; he has pulled dynasts down from thrones and exalted the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty. He has given aid to Israel his servant, remembering his mercy, just as he promised to our fathers, to Abraham and to his seed, throughout the age.’

The Magnificat as it appears in the Book of Common Prayer (1559)

My soule doth magnifie the lorde. And my spirite hath rejoyced in God my savioure. For he hathe regarded the lowelinesse of hys handemaiden. For beholde, from henceforth all generacions shal cal me blessed. For he that is mightye hath magnified me, and holy is his name. And his mercie is on them that feare him throughoute all generacions. He hath shewed strength with his arme, he hath scatered the proude in the imaginacion of their hartes. He hath put down the mightie from their seate : and hath exalted the humble and meeke. He hathe filled the hungrye, with good thynges : and the riche he hath sente awaye emptye. He remembring his mercie hath holpen his servaunt Israel : as he promised to oure fathers, Abraham and his seede for ever.

ADDRESS

Scattering the proud in the imagination of their hearts; putting down the mighty from their seat; exalting the humble and meek; filling the hungry with good things — an Advent address written to outline the task before a progressive, liberal-religious, free-thinking community following Thursday’s General Election (2019)

As we move through the Advent season and head on towards Christmas Day, the annual arc of the Christian story means a woman comes into view, namely Mary the mother of Jesus.

But what do we see? Well, for centuries all we saw was what Luke and Matthew tried to get us to see. It’s important to realise that what they showed us was born out of their need to firefight the scandal that Mary had become pregnant before her marriage to Joseph. Since the Third Century CE — thanks in part to a lost work (‘The True Word’) by a certain anti-Christian Greek or Roman philosopher ‘Celsus’ some which was preserved by ‘Origen’ in his own counterblast, ‘Contra Celsus’ — the rumour has persisted that Jesus’ real father was a Roman soldier, a centurion named Pantera. But whether or not this claim is true — and we simply do not know — the question for Matthew and Like remained: how did Mary become pregnant? Was she was raped, did she have a consensual one-night fling, or was she a prostitute?

For the early, highly patriarchal, morally squeamish Jewish-Christian tradition all of these human options were problematic and, because they couldn’t quash the persistent rumour, a new story, some alternative fact, had to be brought into being.

Given that, in the minds of Matthew and Luke, and in the minds of their readers also, Jesus’ was much more than a mere human being — indeed by this time he was well on his way to becoming the second person of the Trinity’, very God of very God’ — the alternative fact became that Mary was a virgin and that Jesus had been conceived by God through the power of the Holy Spirit. This was why in the Catholic, Eastern and Orthodox traditions she later came to be is believed to be the ‘Theotokos’, literally the ‘God-bearer’ but nearly always translated as the ‘Mother of God’, a being who, in an even later tradition, was believed finally to have been taken up bodily into heaven during an event known as the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (15 August).

In short, by the middle of the first millennium CE, Mary was coming close to becoming the feminine face of God, a fourth member of the Godhead, now not a Trinity but a Quaternity. The Catholic, Eastern and Orthodox traditions have always resisted the deification of Mary but it is not clear to me that they succeeded. To enter into many of their churches (especially those dedicated to Mary) is, instantly, to lose sight of almost any other depiction of the divine but Mary.

In a way we shouldn’t be surprised by this process of deification because the figure of Mary has been inextricably intertwined with the much older goddess Aphrodite/Venus who was herself inextricably intertwined with the even earlier Near and Middle Eastern goddesses Ishtar, Inanna and Astarte. As the historian Bettany Hughes notes in her recent, lovely book ‘Venus and Aphrodite: History of a Goddess’ (Hachett, 1919, pp. 142-144), we need to be alert to that fact that with the loss of belief in the Greek and Roman gods Aphrodite/Venus was not destroyed but ‘simply shape-shifted once more.’ Hughes notes that, because ‘humans wanted the comfort and stimulation of a strong, sympathetic, female presence as an intercessor with the supernatural world’ Aphrodite/Venus ‘survived the Christian revolution — in no less a guise than the Virgin Mary herself.’ Hughes gives a number of examples of this but, here, one will suffice, a Christian church in Cyprus, dedicated to All-Holy Mary, the Church of Panagia Katholiki, which was built in the centre of Aphrodite’s precinct at Palaeo Paphos in the twelfth century. Hughes writes:

Old women with health issues or young women with fertility problems still come there to make small offerings at the pagan stones used to build the Orthodox church: cups of milk, pomegranates, little cakes. Their votive gifts are strikingly similar to those from votaries who came here to worship the goddess over 3,000 years before. In many ways, particularly in the East, Mary of Nazareth was the ancient, teenage, mother goddess — her face unchanged — enjoying an outing in new clothes: the medieval population of Christendom did not want to risk losing contact with a sublime female creature whose powers of cohesion and union were becoming ever more relevant.

But since this deification of Mary occurred, for the most part any way, in patriarchal cultures this has contributed to the creation of many, many, nasty knock-on problems. Putting Mary (or Aphrodite/Venus) on a pedestal and worshipping her was for many men, understandably and not necessarily problematically, a highly attractive thing to do. However, when that elevation occurred in a context of male power and control and which continued to foster guilt about erotic, sexual desire and, of course, sex itself, this has given birth to some nasty, weird and destructive developments. Writing of the pornographic tradition in western art, John Berger described the projection of artists who ‘painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure’.

This reminds us that in our own culture the deification of Mary has simultaneously contributed to a vicious, moral condemnation of womankind which continues to infect our public and private lives. For instance, I particularly worry that in our own ecologically panicked age there is a real danger that Mary/Aphrodite/Venus, in the form of a deified ‘Mother Earth’ (Gaia), may be subjected to the same fate. Indeed, this danger has been seen clearly by the contemporary British philosopher, Timothy Morton (b. 1968) who, in his book ‘Ecology Without Nature’ (Harvard University Press, 2007, pp. 4-5), wrote:

Putting something called Nature on a pedestal and admiring it from afar does for the environment what patriarchy does for the figure of Woman. It is a paradoxical act of sadistic admiration.

Inevitably — especially when the woman concerned is a single mother as was Mary and who, not incidentally, was also a refugee — this path to sadistic admiration for womankind also plays out in our contemporary social and political worlds. We need to remember that we are now being led by a political class of people (mostly men) who have been profoundly shaped by just such a misogynistic, patriarchal and nationalistic culture that despises not only women but also refugees and migrants as being decidedly second-class people, if not much worse.

Alas, it has long been thus, and we may quite legitimately suppose that two-thousand years ago Mary was at the painful, receiving end of similar vitriol and hate from the powerful men around her, men who were also quite happy to describe her as ‘uppity and irresponsible’ for getting pregnant out of wedlock and whom they would have been content to describe as being ‘ill-raised, ignorant, aggressive and illegitimate’ (Boris Johnson, ‘Spectator’ column dating from 1995).

[As Jesus said, ‘If anyone has ears to hear, let them hear’ (Mark 4:23).]

It’s neither difficult nor illegitimate to imagine Mary being torn one way by feelings of depression and despair at her condition and torn another way by a righteous anger at the brutal, injustice of it all. And, although I have been very critical of Matthew and Luke’s creation of the alternative fact that is the virgin birth, I remain convinced that in the words of Mary’s song, the Magnificat, Luke succeeded in keeping alive in the Christian tradition words that the real, human Mary could have spoken; true, angry and revolutionary words. Here they are again (in modern spelling) as I learnt and often sung them as a choir-boy in the version found in the Book of Common Prayer in all it’s versions and as I listened to them only yesterday afternoon in five settings by Herbert Howells and one by Gerald Finzi:

My soul doth magnify the Lord : and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded : the lowliness of his handmaiden. For behold, from henceforth : all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath magnified me : and holy is his Name. And his mercy is on them that fear him : throughout all generations. He hath shewed strength with his arm : he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seat : and hath exalted the humble and meek. He hath filled the hungry with good things : and the rich he hath sent empty away. He remembering his mercy hath holpen his servant Israel : as he promised to our forefathers, Abraham and his seed for ever.

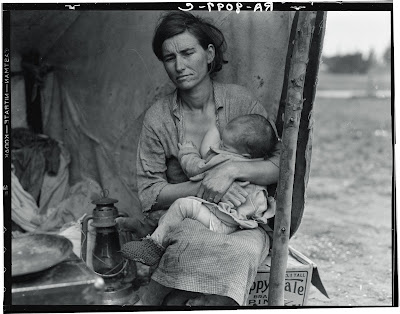

It is plain as a pikestaff that ecologically, politically and religiously speaking we have some very, very difficult years ahead of us. Given this, and given our Greco-Roman, Christian and Humanist history, I would suggest that, without deifying her in the way we once foolishly and problematically did, we will be immeasurably strengthened in so far as we can once again learn to see God, the creative, divine and sacred spirit of life in the faces of a refugee human mother and her child. As we look at them whether as depicted in the etching of the painting of Mary and Jesus by Raphael (1483–1520) that was so beloved by nineteenth and early twentieth-century humanists (see picture at the head of this post), or in Dorothea Lange’s (1895-1965) famous photographs of depression-era migrant mothers (see photo immediately above), especially those of the Cherokee Indian woman from Oklahoma, Florence Owens Thompson (1903–1983), may we not legitimately see there a symbol of the revolutionary power of cohesion and union that we so desperately need to access in our own age?

It is plain as a pikestaff that ecologically, politically and religiously speaking we have some very, very difficult years ahead of us. Given this, and given our Greco-Roman, Christian and Humanist history, I would suggest that, without deifying her in the way we once foolishly and problematically did, we will be immeasurably strengthened in so far as we can once again learn to see God, the creative, divine and sacred spirit of life in the faces of a refugee human mother and her child. As we look at them whether as depicted in the etching of the painting of Mary and Jesus by Raphael (1483–1520) that was so beloved by nineteenth and early twentieth-century humanists (see picture at the head of this post), or in Dorothea Lange’s (1895-1965) famous photographs of depression-era migrant mothers (see photo immediately above), especially those of the Cherokee Indian woman from Oklahoma, Florence Owens Thompson (1903–1983), may we not legitimately see there a symbol of the revolutionary power of cohesion and union that we so desperately need to access in our own age?

As an advocate of certain varieties of contemporary feminist theology, philosophy and politics it has long struck me that if we can find ways to make these images of mothering central to our ecological, political and religious-humanist gatherings, prayers, meditations and rituals, then I feel sure they can help inspire us to continue to try to do what our patriarchal, wealth- and power-hungry Christian tradition has done its level best to stop Mary and her son Jesus doing for two millennia, namely, to scatter the proud in the imagination of their hearts, to put down the mighty from their seat, to exalt the humble and meek, to fill the hungry with good things and, finally, to be able to send empty away the rich and powerful people who believe that they have been born to have power over us.

Only when we have finally succeeded in turning the old, patriarchal world-view upside down — just as Jesus overturned the money changers tables in the temple — will we meaningfully begin to have genuine hope that the words of the ancient hymn also quoted by Luke may, at last, begin to come to pass: ‘Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace among those whom he favours!’ (Luke 2:14).

So, Hail Mary (Aphrodite/Venus), the fully human, humanist, migrant material mother (alma mater), for she is full of grace and revolutionary fervour that can help us bring about equality, justice and peace for all people.

Amen.