A world without gain? An address for Fairtrade Fortnight meditating on a thought by Karl Polanyi and with an after-thought drawn from Paul Mason

Mark 8:35-37 trans. David Bentley Hart

[Jesus said:] For whoever wishes to save his soul will lose it; but whoever will lose his soul for the sake of me and of the good tidings will save it. For what does it profit a man to gain the whole cosmos and to forfeit his soul? For what might a man give in exchange for his soul?

Mark 12:28-31 trans. David Bentley Hart

And one of the scribes, approaching, hearing them debating and perceiving that he answered them well, asked him, “Which commandment is first among all?” Jesus answered: “The first is: ‘Hear, Israel, the Lord our God is One Lord, And you shall love the Lord your God out of your whole heart and out of your whole soul and out of your whole reason and out of your whole strength.’ The second is this: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself.’ There is not another commandment greater than these.”

No society could, naturally, live for any length of time unless it possessed an economy of some sort; but previously to our time no economy has ever existed that, even in principle, was controlled by markets. In spite of the chorus of academic incantations so persistent in the nineteenth century, gain and profit made on exchange never before played an important part in human economy. Though the institution of the market was fairly common since the later Stone Age, its role was no more than incidental to economic life.

We have good reason to insist on this point with all the emphasis at our command.

[. . .]

The outstanding discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships. He does not act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the possession of material goods; he acts so as to safeguard his social standing, his social claims, his social assets. He values material goods only in so far as they serve this end. Neither the process of production nor that of distribution is linked to specific economic interests attached to the possession of goods; but every single step in that process is geared to a number of social interests which eventually ensure that the required step be taken. these interests will be very different in a small hunting or fishing community from those in a vast despotic society, but in either case the economic system will be run on noneconomic motives.

[. . .]

Broadly, the proposition holds that all economic systems known to us up to the end of feudalism in Western Europe were organized either on the principles of reciprocity or redistribution, or householding, or some combination of the three. These principles were institutionalized with the help of a social organization which, inter alia, made use of the patterns of symmetry, centricity, and autarchy. In this framework, the orderly production and distribution of goods was secured through a great variety of individual motives disciplined by general principles of behavior. Among these motives gain was not prominent. Custom and law, magic and religion co-operated in inducing the individual to comply with rules of behavior which, eventually, ensured his functioning in the economic system.

The complete text of Chapter 4 can be found at this link.

—o0o—

A world without gain?

An address for Fairtrade Fortnight meditating on a thought by Karl Polanyi and with an after-thought drawn from Paul Mason

In order to take a view on what ‘fair-trade’ might be it’s important firstly to have a sense of what ‘trade’ has been, is and might be. (One should also interrogate ideas about in what consists fairness but today I leave that somewhat in the background — but keep this in mind throughout this highly provisional, occasional piece!

As with all things, context is everything, and in what consisted trade in the stone-age is clearly not in what trade consists in the market-economy that obtains in our modern and very unstable capitalist age.

To do this, in a moment I’ll turn to a single thought by Karl Polyani whose work is currently being critically reassessed in the morally/ethically aware economics that have begun to reappear following the financial crisis of 2008 which revealed so starkly and shockingly the criminal a- and immoral nature of our modern markets. (See HERE and HERE for examples).

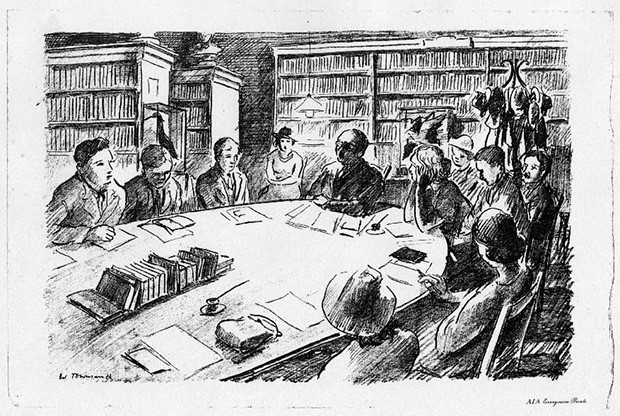

Karl Paul Polanyi (1886–1964) was an Austro-Hungarian economic historian, economic anthropologist, economic sociologist, political economist, historical sociologist and social philosopher. Like many people of Jewish religious heritage, generation and nationality, in 1933 he was forced to flee Vienna and, coming to London, he soon began to work as a lecturer for the Workers Educational Association (WEA) and it was during this period that he began to write notes for the book for which he is chiefly remembered, ‘The Great Transformation.’ In 1940 he moved to the USA where, after a spell teaching at Bennington College, Vermont, he obtained a teaching position at Columbia University (1947–1953) and it was in the USA, in 1944, that ‘The Great Transformation’ was finally published.

Now, before directing your attention to just one of Polanyi’s key ideas in that book it’s important gently to place before you a couple of reasons why taking at an economic issue in the context of a Sunday address in a church is entirely appropriate.

First a general point. My most influential teacher at Oxford and now an old friend, Victor Nuovo, was himself taught not only by one of my own theological heroes, Paul Tillich, but also by the hugely influential theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) and it was through Victor that I came to learn about, and then share, Niebuhr’s concern to utilize the resources of theology to argue for what he called a ‘political’ and/or ‘Christian realism’.

Niebuhr’s ‘Christian realism’ was a political theology which rested on three biblically derived presumptions: the sinfulness (or at least radical imperfectability) of humanity, the freedom of humanity, and the validity and seriousness of the Great Commandment uttered by Jesus which we heard once again in our readings. Alongside this, Christian realism’s two key political concerns were centred on the need to develop appropriate balances of power and political responsibility.

As we proceed it’s important to be aware that Niebuhr believed the kingdom of God could never truly come about on earth because of the innately distorting tendencies of society and, because of this, he thought we must, in certain careful and measured ways, be willing to compromise the ideal of kingdom of God on earth. This attitude is, of course, what makes him much more of a reformist than a revolutionary.

Now, although neither Victor nor I any longer share Niebuhr’s Christian metaphysics — we share instead a passion for slightly different varieties of a Lucretian/Epicurean inspired materialism — we have both continued to admire Niebuhr for encouraging us to find practical ways by which we may ‘moderate our passion’, become ‘reflective, self-critical’ and, in the process, become willing ‘to pursue more modest, realistic goals’ than we are tempted to pursue when we remain in thrall to wholly dogmatic, utopian political, economic and/or religious ideologies.

In all this one of Niebuhr’s basic concerns was to articulate a theologically informed political realism and this is something I continue to share with him because, for me, theology remains through and through political and, although it is often not realised, politics also remains through and through theological. [I was interested to hear the historian Tom Holland make a similar point on the Today programme on Friday morning.] Anyway, as I have often said from this lectern, it is my considered opinion that even long after the death of God — and certainly the death of the kind of supernatural God of theism in which Niebuhr believed — God’s ghost continues to haunt our political structures, all of which, we must remember, were first constructed in ages when belief in God was very much alive. What is true of theology and politics is, naturally, also true of theology and economics because how you believe the world is/should be and what you believe our place to be within that world is/should be has a major effect upon the kind of economic systems one believes are best suited to bring about, for Niebuhr the best possible approximation to the kingdom of God on earth or, for someone like me, the best possible approximation to a federal republic of heavens on earth.

Now, Karl Polyani was a person whose own economic thinking was directly related to this general school of thought. For him the connection between religion, morality, politics and economics came into view in 1917 whilst he was recovering from typhus during which he read the New Testament.

The experience caused him to convert to Christianity and, for a while, even to leave behind political activism. Although it seems he was he was never much of a church-goer and was never associated with a particular denomination, we know that he found what he called a ‘revolutionary’ message in the Christian tradition. In a recent article on Polyani for ‘The Nation’ magazine Nikil Saval writes:

‘The Gospels offered, in Polanyi’s words, “the way to a higher life, over and above personal self-interest,” emboldening individuals to “act with uncompromising radicalism, the almost terrifying radicalism of Jesus.” In later years, he came to find the New Testament inadequate, accusing Christianity of having fostered the conditions for the rise of capitalism. But while Polanyi eventually returned to politics, something of this Christian communitarianism would linger in his assessment of the moral costs of the market economy.’

Anyway, in my opinion the whole of Polyani’s ‘The Great Transformation’ is well-worth (re)reading but today I now simply want to concentrate on something about which he writes in Chapter 4, ‘Societies and Economic Systems’ which, I hope, will help you over the next couple of weeks think more critically about the ‘trade’ part of the term ‘fair-trade.’

As you heard in our readings Polanyi wanted ‘to insist . . . with all the emphasis at our command’ — and for him this emphasis included various historical, sociological and anthropological study of, for example, Kula ring exchange in the Trobriand Islands — that the market prior to our own 20th century (and now 21st century) age ‘was no more than incidental to economic life.’ Polanyi argued that there were three basic types of economic systems which existed before the rise of our own societies based on a free market economy: redistributive, reciprocity and householding.

1. Redistributive: trade and production is focused to a central entity such as a tribal leader or feudal lord and then redistributed to members of their society.

2. Reciprocity: exchange of goods is based on reciprocal exchanges between social entities. On a macro level this would include the production of goods to gift to other groups.

3. Householding: economies where production is centred on individual households. Family units produce food, textile goods, and tools for their own use and consumption. (Source).

It is important to realise that Polanyi these were never mutually exclusive systems, nor were they ever mutually exclusive of markets which were concerned to facilitate the exchange or trading of goods.

However, the key thing to grasp here is that all of these three forms of economic organization were based around the social aspects of the society they operated in and were explicitly tied to do those social relationships and, as Polyani notes ‘[t]he outstanding discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships’ (my emphasis).

Polanyi is clear that in earlier societies’ economic systems, individual humans — men in Polyani’s terminology — were not concerned ‘to act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the possession of material goods’, rather ‘he acts so as to safeguard his social standing, his social claims, his social assets. He values material goods only in so far as they serve this end.’

As Polanyi continues:

In this framework, the orderly production and distribution of goods was secured through a great variety of individual motives disciplined by general principles of behavior. Among these motives gain was not prominent. Custom and law, magic and religion co-operated in inducing the individual to comply with rules of behavior which, eventually, ensured [a person’s] functioning in the economic system.

And here we are at the key point I want to bring before you in the context of ‘fair trade’ fortnight. It is to see that in the all human economies until our own age ‘gain was not prominent.’ Here’s what Polanyi says about ‘gain’ in an earlier chapter in the book:

All types of societies are limited by economic factors. Nineteenth-century civilization alone was economic in a different and distinctive sense, for it chose to base itself on a motive only rarely acknowledged as valid in the history of human societies, and certainly never before raised to the level of a justification of action and behavior in everyday life, namely, gain. The self-regulating market system was uniquely derived from this principle. (p. 31)

It is vital to hold in our mind at all times, but especially during Fair-trade Fortnight, that the modern fair-trade movement is embedded wholly within a market system in which ‘gain’ is the central principle.

To begin to draw to a close, now recall that Polanyi felt we should try to ‘act with uncompromising radicalism, the almost terrifying radicalism of Jesus’. Then also recall that Jesus was powerfully concerned to challenge the idea that our relationships with each other should have ‘gain’ as their central principle. Indeed, Jesus’ words strongly imply that when we give in to the desire for ‘gain’ we forfeit our very soul.

Jesus preferred to encourage us to understand our relationships with each other in terms of ‘exchange’ asking: ‘[f]or what might a man give in exchange for his soul?’

And, here we find ourselves back in a pre-market economy world where our relationships with each other — including the relationship of trade — were framed not in the social terms of gain but in terms of redistribution and reciprocal exchange between local economies.

This morning — especially in a moment when, thanks to intervention of coronavirus the global market economy looks like it’s about to have a very serious wobble equal to or even significantly exceeding the one it experienced in 2008 — I think our reflections on Polanyi and Jesus presents us with a question upon which we should be very seriously meditating and which is as much moral as it is economic, namely:

What would fair-trade look like in a world that had been able to free itself from the motive ‘gain’ as its central principle and which has an economic system run on noneconomic motives and which organizes itself on the principles of reciprocity or redistribution, or householding, or some combination of the three?

Remembering Niebuhr here, I’m sure that were we — by design or thanks to unpleasant contingent events — to achieve this kind of change it would not, of course, bring about a kingdom or federal republic of heavens on earth, and compromises to our ideal would still need to be made. However, ridding ourselves of our recent, world destructive obsession for gain would surely help make the world a moderately better and fairer place in which to live.

—o0o—

An Afterthought

In the conversation in the service itself immediately after the address and at the bring and share lunch in the church hall afterwards (which had as its theme Fairtrade) I was encouraged by a number of those present to suggest my own tentative answer. My personal preference is to proceeding in ways very, very close to those suggested by Paul Mason in his books Postcapitalism: A Guide to our Future and Clear Bright Future: A Radical Defence of the Human Being.

As a hint at what that might mean in the context of this address are the (for me, magnificent,) three final paragraphs of his chapter from Clear Bright Future called “What’s Left of Marxism” (there is, of course, a pun in play here . . .):

So here’s how I would answer the question: ‘are you a Marxist?’

I am a radical humanist who thinks we’re on the cusp of achieving something Marx wanted: a technologically enabled society in which most things are consumed for free, and the alteration of human beings on a mass scale in order to take advantage of such freedom. Like Marx, I believe this propensity to achieve freedom is the product of our evolution, and every recent advance in genetics, evolutionary biology and neuroscience reinforces that belief. Like Marx, I believe the socialization of knowledge through technological progress will bring us up against the limits of a society based on private property.

But unlike Marx, I believe this human revolution will be achieved not by the blind actions of a single class, but by a diffuse network of human beings acting consciously. Unlike Marx, I believe the planet creates limits to the way humans should use technology and mandates certain priorities in the transition beyond capitalism. And unlike Marx, I don’t laugh out loud at the words ‘moral philosophy’ — because the nature of the technology we will rely on to achieve abundance means we need a global ethical framework to keep it under our control (p. 242).

As an erratic Marxist myself I can wholeheartedly say ‘Amen’ to this!

I also note with pleasure and gratitude that, immediately prior to the words quoted above, Mason writes of the need for secular humanists like himself to “acknowledge — and be proud of — the continuity of our ideas with the human-centred religions of the Axial Age, and with the Judaeo-Christianity of the Enlightenment” (p, 241). As a minister of a church tradition rooted in the ideas of the Enlightenment (especially Spinoza) I appreciate and accept his hand of friendship and acknowledge that, in return, we must reciprocate by acknowledging and being proud of the continuity of our ideas with the non-religious and atheist, humanist traditions of Greece and Rome and the Enlightenment.

As someone once wisely said: when we don’t mind who takes the credit there is no end to what we can achieve together.